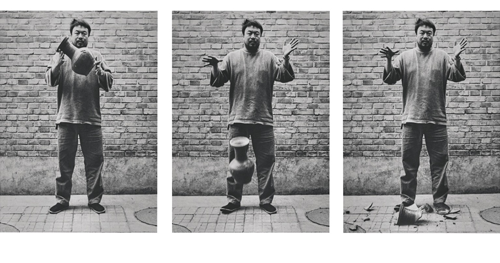

“Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995) by Ai Weiwei. Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Once seen, it can never be forgotten: the defiant face of Ai Weiwei as he drops a 2,000-year-old urn, letting it shatter at his feet. Ceramics have come to represent Chinese history more than any other art form, so the outcry that followed Ai’s performance and his invocation of the Cultural Revolution slogan Smash the four olds! was hardly unexpected — but for all the brouhaha, the work marked the beginning of a new centring of ceramics in Chinese contemporary art. This is not to say, of course, that a rash of blanc de chinestatues were eased off cliffs, or celadon bowls tied to train tracks, but that young artists began to look to this traditional medium for inspiration.

Ceramics have always been placed atop the theoretical border wall dividing art and craft, with the advantage that they can easily be appropriated by both sides. Ai was responsible for the 2010 crossover piece Sunflower Seeds, in which he filled the turbine hall of London’s Tate Modern with millions of seeds made by artisans from Jingdezhen, centre of Imperial porcelain production. (Mao Zedong often depicted himself as the sun, and his painfully oppressed people as sunflowers.) Between 2007 and 2009, meanwhile, the legendary painter Chu Teh-Chun decorated 27 white Sevrès porcelain vases with gold and cobalt blue, working on each for 300 hours until they were “no longer objects of ornamentation but…pictorial works of meditation”. Far from occupying a hazy middle ground, ceramics have the potential to serve as both canvas and content.

Other Chinese ceramicists have concerned themselves with a different (and of course, potentially false) dichotomy, that of tradition versus modernity. Li Lihong’s Coke and Absolut vodka bottles are dressed as blue and white or sancai wares, while elsewhere he disguises the M of the McDonald’s and MTV logos as masterpieces in famille jaune and famille vert. The pieces are often displayed in groups, more discount supermarket than hushed museum, and it is hard to discern whether Li embraces these global brands or regrets their inevitable journey east. In a similar vein, Wan Liya decorates household containers such as milk cartons and pump-spray bottles in the famille rosestyle, mingling the mighty and the mundane. Superficial representations of China, Wan suggests, and especially those that rely on past glories, may be at odds with the reality of ordinary people’s lives.

“Absolut China” (2004) by Li Lihong. Image courtesy of Hollis Taggart Galleries.

While artists like Li and Wan mimic traditional craftsmanship, there are also prominent craftspeople whose work looks decidedly like contemporary art. Su Yongjun of Shanxi province hit the headlines when an ancient Su-style roof tile was discovered during renovations at the Forbidden City, and he decided to resurrect the 700-year-old family business in Taiyuan with a focus on sustainable methods. Su worked for two years to perfect a formula for peacock blue glaze using only mineral ingredients, with the resulting wall tiles recalling Fauvist experimentation. Su-style ceramics have now been listed by the Ministry of Culture as part of China’s intangible cultural heritage.

Tiles by Su Yongjun (2017). Image courtesy of Blue Ocean Network.

Tiles, like Ai’s sunflower seeds, cannot help but suggest infinite replicability, so the paradox of producing such items by hand is compelling and never more so than in the work of Xu Hongbo. About his Clones series, in which porcelain babies tessellate in clumps or appear pickled within celadon tiles, Xu says, “In our age of information [and] industrial production, it appears to me that the most important characteristic is that of reproducing. There seems to be greater value placed on quantity over quality. Perhaps it is because quantity seems absolute while quality seems relative.” He articulates a central concern for the new breed of ceramicists: the lightning speed at which China has been forced to absorb capitalist practices, setting doubt and even discomfort aside.

“Clone05 — Birth Dates (Angel Wall)” (date unknown) by Xu Hongbo. Image courtesy of Saatchi Art.

And then there is Geng Xue. In 2014 Geng pulled ceramics in an unprecedented direction by placing them centre-stage, and in extreme close up, within her video work. The stop-motion film Mr Sea attempts to capture the essence of Pu Songling’s eighteenth-century stories, Strange Tales from Make-Do Studio, using porcelain puppets and props. Songling aimed through his writing to raise awareness of injustices suffered by the poor, and as Geng’s dolls move through their delicately waterlogged world, it is impossible not to consider the millions of workers today on whose cut-price labour China’s future depends. Geng’s blue and white porcelain actors, tenacious but fragile, seem uniquely placed to star in this tale.

How might these pioneering ceramicists fit into the history of art in China, which has been characterised by continuous tradition? The new movement in ceramics is both democratic and receptive in a way that has rarely been seen. For centuries, ceramics were not available to working people; they were produced only for emperors, either for their personal pleasure or to use as diplomatic gifts, or they were exported overseas. The names of individual artists were not recorded, particularly as industrialisation advanced, so it is no overstatement to say that these are the first ceramic workers whose identities will be known.

It is also true that, in the past, cultural contact tended to proceed in one direction; Chinese greenware was copied and developed in nearby South Korea, Japan and Thailand, while the export of Ming porcelain in the seventeenth century may have influenced azulejo tile-work in nations as distant as Portugal and Spain. But until recently, on any discernible scale at least, artists in China have been slow to incorporate foreign innovation, preferring either to reproduce it directly (consider the phenomenon of copycat architecture — Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp Chapel now has a spooky twin in Zhengzhou) or absorb it in secret. In Chu Teh-Chun’s use of French porcelain, or Li Lihong’s effigies of Western products, a genuinely intercultural dialogue is allowed to occur. As it turns out, there’s more than one way to smash an old.