What is it to inherit an age-old painting tradition? For one young artist, sticking to her principles are now more important than ever.

In the bustling metropolis of Shanghai, an artist named Seqinglamu had just completed her life’s work. Barely twenty-one years old, and brimming with optimism, she was finally graduating after eight years of diligent study in her home county of Rangtang. Her graduation piece, an intricate painting of Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, had astonished serious art collectors worldwide, though Seqinglamu wasn’t much concerned with what they had to say.

Graduation of Jonang Thangka Students Seqinglamu - Jonang Thangka Student

After such dedication to her art, Seqinglamu knew better. The phone calls, the visits, the praise, the bright lights of the city: no matter what it was, it was irrelevant. She had inherited a Tibetan Buddhist art discipline called Jonang Thangka, a painting art originally serving the imperial courts of the Ming dynasty and Qing Dynasty and therefore having the highest artistic value among all the Thangka schools.. She simply wanted to continue perfecting the ancient painting techniques she had practised under the watchful eye of Jianyang Lezhu Rinpoche, her mentor at the Jonang Culture Center, an institution set up in Rangtang Town.

Along with fifty-nine other students, who also hailed from the green landscapes of the Sichuan province, Seqinglamu had been taught the importance of the art form as a meditative tool. These depictions of Buddhist deities have been used as a medium for prayer and ritual for years, and nothing—not even worldwide acclaim—could change that history; Jonang Thangka is regarded as having the highest artistic value of any Thangka painting.

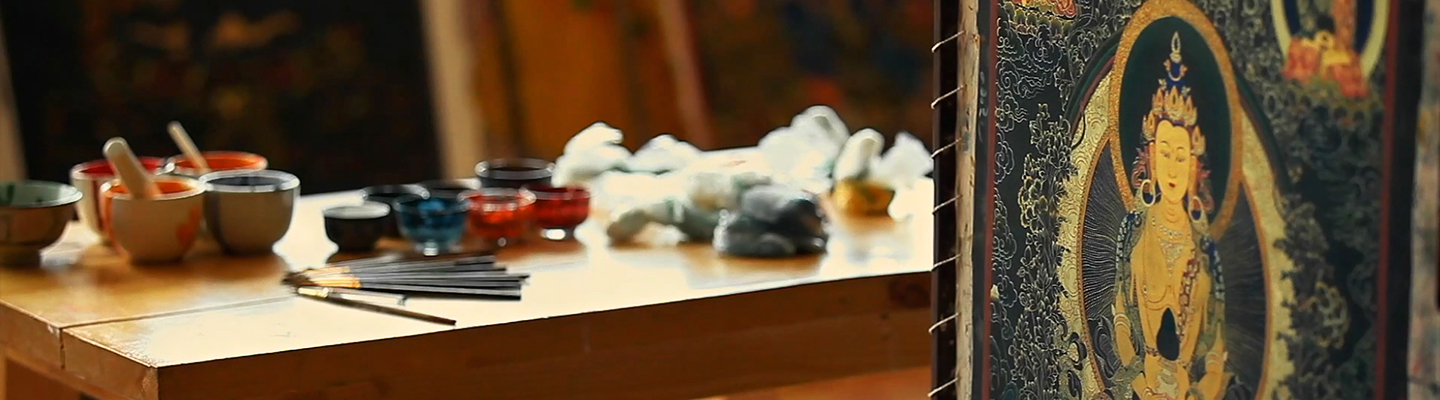

Students painting Jonang Thangka Jonang Thangka

Older generations continue to pass down cultural heritage in every corner of the globe. In West Africa, singers and storytellers known as griots or jalis have a long and unique history of preserving their musical heritage. Across ten or more countries—in Mali, Senegal, Guinea, and Burkina Faso, among others—griot families teach fresh generations traditional songs and expand their knowledge of local history, effectively making them oral historians as much as performers.

With Jonang Thangka painting, there are similarities. At Jonang, Rinpoche imparts history and knowledge to his students, and although they may not be from the same extended family, as in griot culture, this is still very much an exchange of local culture between old and young—a culture that would be consigned to the past unless people like Rinpoche treated it with respect.

There are comparisons, too, with the religious aspects of both traditions. In griot culture, praise songs about gods, men, animals, and nature, have been adapted through time and between age groups, though they remain about the same subjects. It is also true of Jonang Thangka, in the sense that the art style is based upon Buddhist teachings; and although each piece of art is unique in its own way, the core principles remain the same.

There are certain traditions, globally, that have evolved with each new generation of inheritors—sometimes beyond recognition. In the case of Yoga, the spiritual and physical practices which originated in ancient India, the way in which it is practised in the West today can often bear little resemblance to its original forms. This makes sense given how recently it was introduced to the West: at the earliest it was brought in the late nineteenth century by Swami Vivekananda, who was born in what is known today as Kolkata.

Jonang Thangka is quite different: Whereas Yoga has spread across continents as a widely practised discipline, Jonang Thangka began in the Ming Dynasty before its teachers and monks escaped to Rangtang during Qing Dynasty and began passing down their art centuries ago. In comparison to Yoga, it hasn’t spread a great distance, and its practitioners are far fewer in number. Most crucially, though, Jonang Thangka art itself hasn’t changed drastically. Its format—usually painted on cotton or silk—is the same as it was in the eighth century, and its function as a tool for self-development and spirituality remains completely intact.

There are a number of reasons for these things. First, it can take up to six months to finish a Jonang Thangka painting, but several years to hone the skills necessary to complete one. Because of this, it is only the most dedicated students of the art discipline that will become its inheritors. Second, Jonang Thangka hasn’t seen nearly the same kind of popularity worldwide, perhaps because it is such a difficult skill to learn—let alone master—mainly taught in Buddhist institutions.

Whether Thangka is a skill alone remains a point of contention, as Rinpoche told BON Cloud, an English language media company based in China: “I don’t regard Thangka as a craft or skill, but a way of understanding my own body and mind.” This is a process of introspection, one of unique self-control, and as Maia Gambis wrote in the Washington Post in 2015, creating art is a “way to access a meditative state of mind and the profound healing it brings.”

Jianyang Lezhu Rinpoche

Jonang Thangka, then, is an interesting kind of meditative process. Paraphrasing Robert Wright, author of Why Buddhism Is True, columnist Adam Gopnik described meditation as “the draining away of the stories we tell compulsively about each moment in favor of simply having the moment.” While that idea might seem universal, it can be argued that, for a Jonang Thangka artist, the painting process is about having that moment through telling the story of a separate moment—often one of great religious significance.

Jonang Thangka Pigment Seqinglamu - Painting Jonang Thangka

Depicting a moment of the Buddah’s greatness, as Seqinglamu did in such glorious detail, is a pure example of the passing down of cultural heritage, untainted by any significant change in the discipline over a long period of time. Her humble reaction to the success, as much as the quality of the art, are each reflections of what she has been taught. Asked about the twenty-one year old’s exploits, Rinpoche responded with characteristic measure: “She has a talent for painting.” Coming from a teacher who regards humility with great importance, this is high praise indeed, and perhaps a sign of things to come.

“The teacher told us that when painting Thangka or doing other things, we should calm our minds,” Seqinglamu had said. “No matter what we do, we should be kind and merciful.”